Richard Miller, Bohemia: The protoculture then and now

Murger and the Creation of a Bohemian Counter Culture

Born on 22 March 1822, Henri Murger grew up an only child in an apartment house where his father kept a tailor shop and served as custodian. . . . He was the pet of the tenants and of his quarter. Determined to rear a gen tleman, his mother dressed him expensively, all in blue, and nour ished his ambitions. At eight, while following the Battle of Hernani, he is said to have resolved to become a great tragic poet. His father expected him to become a tailor. At fourteen, the elder Murger took him out of school and into the tailor shop. Although "naturally avid to know and see all," Henri never went back to school. Throughout life he suffered from the effects of a defective education . One friend said he took for new ideas as old as the Parthenon; another remarked that he had learned his reading from street signs and his arithmetic from house numbers.3

Murger formed the center of a group of young men from poor families who sustained each other in their dedica tion to art. In the fall of 1841, they constituted themselves as a formal cenacle, the Society of Water Drinkers. Murger, who proposed the name, was thinking of A Big Man from Province at Paris, a Balzac novel published in 1839 that uses the word bohemian in its new sense and includes the Cenacle of the Four Winds, a group of gifted and idealized youths combined for mutual aid. Noel, Lelieux, then a writer; a youth who was to become a prominent painter; a Polish refugee and some others composed the bohemian cenacle of Water Drinkers.10 Imagine what it must have meant to be poor in Paris in 1841!

Imagine what it would have meant to direct all your passion into the arts, and in a society where anyone with five francs (a silver dollar) "was regarded as richer than Rothschild"11 to give first priority in spending money to art materials! All of the water Drinkers lived in hunger, cold, discouragement, discomfort, and, when they had rooms at all, in attics, because attics for good reason are cheapest. These men did indeed put art before pleasure, materials before food, free time before comfort. It is this pattern of choice that Murger and his friends added to Bohemia.

Henri Murger, Photograph by Nadar (1857)

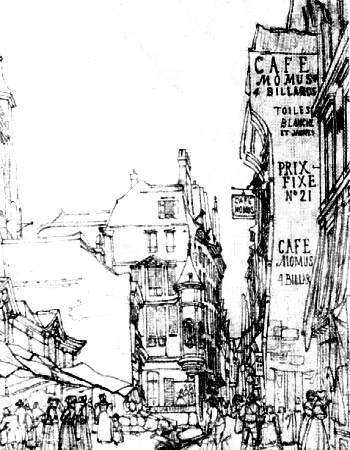

Cafe Momus

Gathered around the noble principle of art-for-art, the Water Drinkers were pledged by their articles of incorporation to pay dues into a mutual-aid fund, to shun political discussions and drink only water at their monthly meetings, and, once a year, to justify their membership by presenting some major work of art.12

Eventually the society cracked in the vise of poverty, but Murger and his intimates kept on seeing each other.

Soon Murger was at the center of another cenacle. Picture him, as he puts it, having a forehead as bald as a knee and an enormous beard, red, blond, black-a tricolor, his face flabby and wrinkled at age twenty-two, sitting with a company of madmen in the upper room of the Cafe Momus.13

Most obvious among the Momusians would be Nadar (Felix Tournachon), a caricaturist and journalist who somewhat later may have taken the world's first nude picture and did take the world's first aerial photograph hovering over Paris in the basket of a bal loon. But these distinctions of Nadar fade before the image of his bright red hair, his staring eyes, his elephantine body. He stood seven feet tall! Once he appeared at a fancy-dress ball in a long dress, string of yellow beads, oilcloth bib-as a baby!

At least two of the regulars were what Murger called amateur bohemians --men pretending to be poor. Other Momusians were Gustave Courbet, a rugged young painter celebrated in art history as the inventor of realism and in political history for his participa tion in the Paris Commune; a man who had just completed a jail sentence for showering socialist leaflets on the audience seated at the Opera; some Water Drinkers; and a clean-shaven, sternfaced poet dressed in black and white: Charles Baudelaire.

From time to time, Gerard de Nerval or Theophile Gautier, now both in their thirties, dropped in.

Once at the Momus, some of Murger's friends invited six wet nurses and six professional pall-bearers to a party. To the nurses they offered milk -- and to the bier carriers they served beer. This provoked a brawl which, in turn, led to the temporary closing of the cafe.

Bohemia seems to have been then, as it is now, a loose, overlap ping structure composed of small societies, cenacles, coteries, and ca bals. Baudelaire, though never a man to follow mutual-aid principles, stood at the center of a group organized by Gautier, established in a hotel behind Notre Dame, called the Haschischiens (the Hashishers), a group that introduced dope into Bohemia with effects resembling those of the introduction of LSD a century later. Fancying he was copying Thomas De Quincey, author of Confessions of an English Opium Eater, and Edgar Allan Poe, whose poetry he had translated, Baudelaire, for quite some time, had been using opium and hashish and, some say, in doing so had originated the romantic image of poet/doper.14

Jean-François Raffaelli, Bohemians at a Café (1886)

By this time the market for writing had expanded enough to afford the Momusians some subsistence. Book publishers and the aters abounded; newspapers, magazines, trade journals bloomed and withered. One of these, La Naiade (The Water Nymph), the organ of bathhouses, was printed on india rubber in indelible ink so the readers could safely take it into the tub.15

Driven by his burning purpose, Murger worked night after night on poetry, which never reached print let alone transformation into fame and fortune. His purpose slowly failed. He thought of suicide. Once he almost joined the navy. He almost accepted a job. He thought of marriage. He would even betray poetry and write prose. "It's all very well for people to paint Bohemia in rosy colors; it will always be a sad and sorry existence." Once he was so hungry that he smoked opium so he could go to sleep. Eventually he became so ragged as to preclude looking for work16.

To a younger friend who in l 845 offered him a post in a pro vincial school, he replied in refusing: "I am on a bad road, as you say, and I am only too well aware of it. I am doing shameful things so I can go on living, and I know it. What's the use? To go on working in spite of everything, to prove to myself that I am, because so far I have not proved this to my satisfaction. I don't go to the theater, the dance hall. I have no mistresses and I live with the austerity of an anchorite. I have only my friends. There is only one good and beautiful thing left in life for me, and that is art."17

Less than a month after this, The Monitor of Fashion invited the ragged Murger to work on its staff. Then he took some poems to The Artist. Murger and its editor, Arsene Houssaye, took an in stant liking to each other. Houssaye, now ten years away from Doy enne, later recalled: "He was pale and worn; he had already come through Bohemia without knowing it. But he complained of nothing except of having to write for a fashion magazine, he whose coat was too old-fashioned for words. . . ."

Houssaye commissioned a short story; the Corsair, whose editor affectionately called his writers- most of whom gathered at the Momus -- his "little cretins," accepted a story. This was the first of the series that made Murger famous enough to be remembered today, a chapter of what was to become Scenes de Boheme (Bohemian Scenes), later also called Scenes de la Vie de Boheme (Scenes from Bohemian Life) and, as an opera, La Boheme (Bohemia). [It may be added that sinc e Miller wrote these words it has become the basis for the musical Rent.]Murger published the next chapter a year later and then chapters followed regularly in Corsair until the last appeared in 1849.19 . . .

Taken all together, Murger's Scenes de Boheme tell of the adventures of Rodolphe (a young poet) , Schaunard (a painter-com poser), Marcel (a painter modeled on Courbet) , and Colline, a philosopher who like Gerard de Nerval carries a library in his pockets. These young men are dedicated to art, for that is what they do and why they accept poverty, but rather than sentimentalize their dedication, Murger mutes it. They never talk about art nor do they feel sorry for themselves suffering the neglect of the world. Their art is anything but holy. Marcel works on a painting called The Passage of the Red Sea. Each year the Salon refuses it and each year Marcel changes the figures, to Romans, to grenadiers, and resubmits it. A pawnbroker-dealer eventually buys it. When Marcel next sees his masterpiece, a steamboat has been added to transform it into The Habor of Marseilles and it is serving as a food importer's shop sign. Rodolphe (who looks like Murger and is Murger) works continuously on a great tragic poetic play called The Avenger; Schaunard struggles to perfect his symphony, "The Influence of Blue on the Arts;" and Colline finally places a philosophical essay -- in Castor, an organ of the hat trade. At one point Rodolphe is locked in a room by his uncle, a stove manufacturer, who refuses to return his clothes or let him out until he has finished editing a tome on the problems of heating. Cold, next to hunger, is Rodolphe's prime problem, but that is not the kind of copy the uncle wants. To evade lodging at the Beautiful Star Inn, Rodolphe accepts any commission, as when he ghost writes a didactic poem called Medical-Surgical-Dentist or when he composes a poetic epitaph for a tombstone. . . .

In serial form, the stories aroused interest but it was not until 1849 when a playwright helped put Scenes de Boheme on the stage that this new symbol began to burn itself into the minds of the general public. Almost all of the models for its characters, society, the press, even President Louis Napoleon, came to the opening. The play was a terrific success. Victor Hugo wrote Murger in congratula tion. Arsene Houssaye boasted of having been the first important editor to present Murger. That very night Michel Levy, the publisher, gave Murger 500 francs in gold for the book rights, an investment which it is said returned to Levy more than 25,000 francs after the book appeared in 1851 . The leading lady gave Murger a ride home in her carriage. Imagine, he said, "what it's like for the first time in your life to find yourself sitting beside a woman who smells nice."20

Prosperous at last, Murger moved into a good flat in a fashion able district and bought a country house. "The silver dollar is the Empress of humanity."21 His mother's wish had finally come true. As country gentleman and man-about-town, he began living a thoroughly bourgeois life, though it must be remembered that for the French with their sharp double standard, a bourgeois life may in clude both mistresses and brothels. . . .

Then in 1858 he enjoyed a real bourgeois triumph, but one which made the obstacle florescent. The Emperor Louis Napoleon appointed the author of Scenes de Boheme to the Legion of Honor. Murger aspired more intensely than ever to the Academy, but that accursed bohemian reputation, those few light stories done to amuse the readers of Corsair, made this appointment impossible.

Early in 1861, suffering terrible pains, Murger went to the hospital. He died in agony. In the procession to the cemetery, men like Gautier and Houssaye walked near the hearse; students and poor young artists trudged at the end. Murger had received a state funeral-at the age of thirty-eight.

Murger was dead, but the bohemian image lived on, at length fixing itself in the mind of romantic youth everywhere. As serial, play, and book, Scenes de Boheme had introduced France to the hitherto unknown lbeit much sentimentalized Bohemian life of the Latin Quarter. . . .